When it comes to history, our understanding is bounded by recognition. We tell ourselves that human nature is in some fundamental ways immutable, so we can understand our ancestors in a way which we cannot claim to understand, say, monkeys or bats.

But I don’t really believe this. When I think of my own family, I feel I have a fairly good understanding of my parents, and I think about the impact their wartime childhoods, and the post-war poverty and rationing had on their attitudes. I am sketchier about my grandparents. I remember them variously as good-humoured but deaf, touchy, and in the case of my grandmother on my fathers side, defensive and scratchy against my mother’s hostility to her. But I don’t feel their youth - who were these youngsters sailing off romantically around the Med in their 20s? Then I get to my great-grandparents. Apart from one, these are unknowns and partially mythical (‘Charles K Taylor - the founder of the family business’) I have no feeling for them, no knowledge of him, and no understanding of what they could have been like.

How many generations do we have to re-wind to get back to the beginning of Barbados, claimed in the name of King James in 1625? I make it about 18. So we’re talking about my great^16 grand-parents.

Who were they, and what were they like?

It is hard to imagine, since we have little folk memory of the 17th century as ‘The Little Ice Age’ - a time when global temperatures fell by one or two degrees celsius, harvests failed, wars proliferated and populations fell. Climatically, the 17th century saw a nasty feedback loop develop. The ‘Maunder Minimum’ of solar activity saw sunspot activity fall first in 1617, partially recover, and then, between 1645 and 1715 there were virtually no sunspots. This dwindling of solar activity seems to have disrupted the typical global pattern of surface air pressure, which in turn generates the El Nino-Southern Oscillation. Today, El Nino typically happens about once every five years, but in the mid-17th century it happened twice as often.

This may have had a further effect: in ‘normal years’ when easterly winds prevail, the Pacific stands some 24 inches higher off the Asian than off the American coast, whereas in El Nino years, those levels reverse. ‘The movement of such a huge volume of water places enormous pressure on the edges of the earth’s tectonic plates around the Pacific periphery, where the most violent and active volcanoes in the world are located.’

According to the Earthquake Catalogue, volcanic activity peaked in the mid-17th century, especially in the ‘ring of fire’ around the Pacific Ocean. If so, the doubled frequency of El Nino could be responsible for a spate of volcanic eruptions which in turn darkened the skies, cooled the climate, and scuppered harvests worldwide.

We have largely forgotten this was dark period of recent human history. But as Geoffrey Parker writes in ‘The Global Crisis’ this was ‘a catastrophe that may have reduced the size of the global population by one-third’.

To give just one example: in the middle of the 17th century, England’s population stood at around 5.25mn, but by the mid 1680s it had fallen to around 4.8mn. The population didn’t recover until around 1715. At the same time, and not by coincidence, the price of wheat bought to feed Eton Collage rose from 20-30 shillings a quarter at the beginning of the 17th century to 55-60 during the Civil War, and 40-50 for much of the rest of the century.

As the cooling of climate took hold, so much of the world discovered it had a food supply problem, or ‘overpopulation’ problem, derived ultimately from the good harvests of the previous century.

A warmer climate in the 16th century had brought marginal lands into production: as the climate cooled, that production failed, with the result that a small climatic deterioration resulted in a large shortfall in harvests. The process was not linear: in Manchuria, where in a good year there are only 150 frost free days, a fall of 2 degrees in summer temperature cuts harvest yields by 80%. In latitudes north of the ‘temperate zone’ each fall of 0.5 degrees cuts the number of days on which crops ripen by 10%, doubles the risk of a single harvest failure, and increases the risk of a double failure six-fold. For those farming 1,000 feet or more above sea level, a fall of 0.5 increases the chances of two consecutive failures 100-fold.

In a good year, a farmer’s family may consume 75% of what he grows, with the other 25% going to market. If the harvest fails, the farmer may survive, but he will have nothing to supply to the market. Cities starve.

As harvest disappoint or fail, so do the structures of charity which were ultimately based on those harvests. Smaller harvests mean smaller church tithes from paid for charitable support for the destitute, just as the numbers of destitute surged.

Again, the collapse of previously viable private charitable structures was seen globally. The result was starvation, not merely in England or Europe, but across the entire globe.

It was against this background that Thomas Hobbes writing in Leviathan in 1651 warned that without despotic central authority, life would be ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’. By that time, life was ‘short’ in two ways: both in duration, but also in size. Frenchmen born in the ‘year without a summer’ of 1675 were the shortest on record, with an average height of just 63 inches (5ft 3’’).

And when your problem is overpopulation, human rights tend to disappear. Geoffrey Parker again: ‘Unless prevented by disability or weakness, until the later seventeenth century most ordinary English men and women started to earn their living at age six or seven and ‘literally worked themselves to death’.

These are the conditions which produced were the people who landed in Barbados in the terrible 17th century.

They were strange and dangerous. Britain was about to embark on a civil war, in which 10%-20% of the male population fought, and which killed approximately 3.7% of the English population, 6% of Scots and a staggering 41% of Irish (caveat - Wikipedia number). One king was also killed.

For comparison: World War 1 casualties (military and civilian) came to 1.9% of the population; World War 2 for 0.9%.

Life was cheap, and stayed cheap for a very long time. In 1762, British forces besieged and took Havana. This entirely forgotten piece of British military history cost the lives of of 7,472 British soldiers and sailors. The outcome? The British sacked Havana and shipped £389,450 worth of gold bullion back to London. To put that in context, it was the equivalent of 71% of Britain’s gold coinage, and 19% of Britain’s gold reserves.

Job done: six months later the British returned Havana back to Spanish rule. 7,472 casualties!

The barely-imaginable cruelties of West Indian chattel slavery were, in the first instance, extensions of cruelties already practiced in Barbados before slavery became common, let alone dominant. In the beginning, the justification for cruelty wasn’t even racist - if any justification for barbarism was thought necessary.

Rather, the cruelties were inflicted on the white immigrants, at first those sufficiently economically distressed to countenance indentured servitude in the West Indies. But later it was people unwillingly shipped to Barbados as prisoners of war (Irish, Scottish), vagrants and criminals, prostitutes (to increase the population) and just plain kidnapped children. Cromwell, in particular, was delighted to be able to raise money by selling Royalist prisoners to the shippers. Later, willing transportation to Barbados could even get you off a death sentence.

Well, perhaps: between around 1650 and 1800, something like a third of all whites died within three years of arriving in the Caribbean.

(Remember this context when we later consider the work of John Locke, the philosophical founder of Western liberalism.)

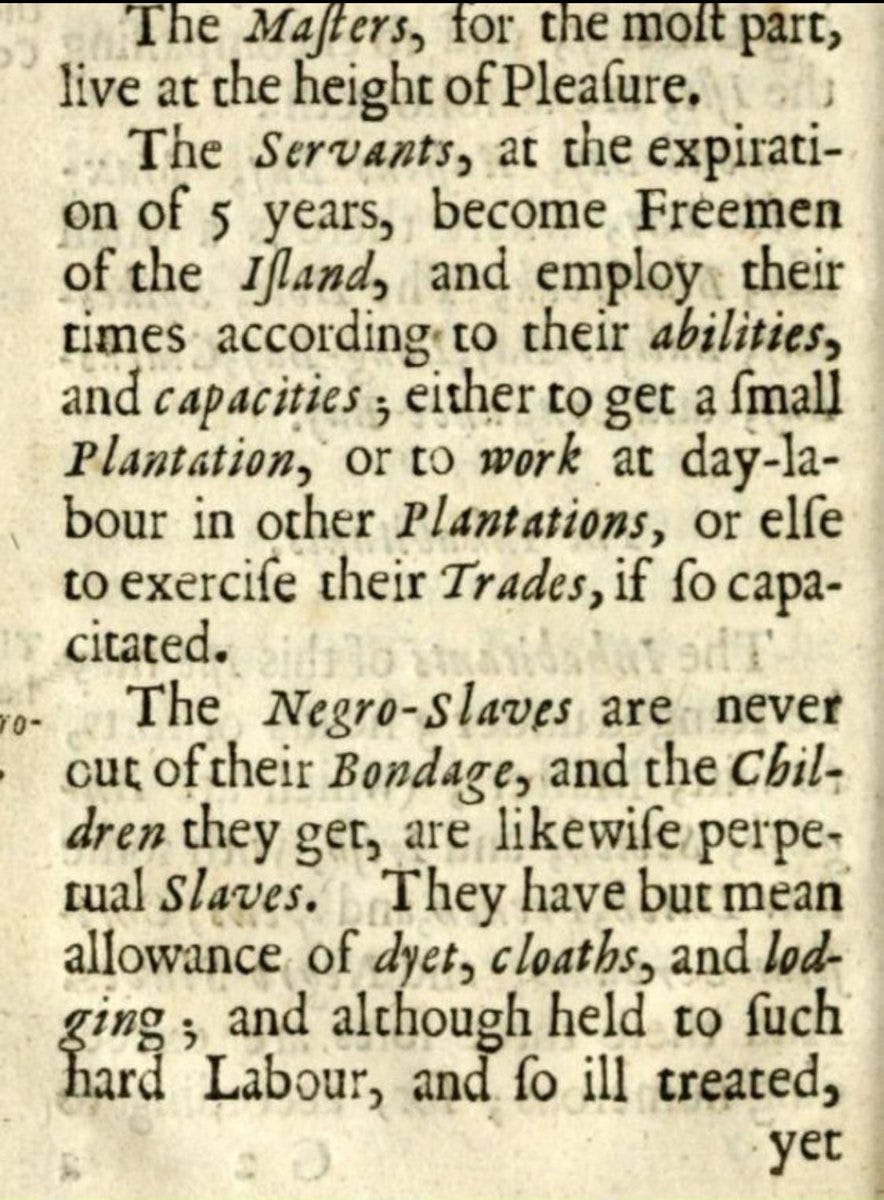

A nasty fate of indentured servitude awaited the new arrivals. In theory, indenture involved a contract to work for a master for a period of time (usually three to nine years). Some indentured servants were paid annual wages, but most were promised a one-off payment, usually around £10 - or some land (10 acres in Barbados) at the end of the contract.

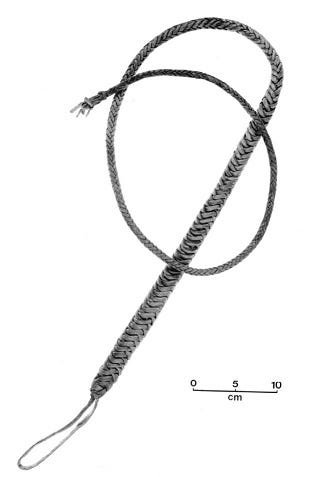

In practice things were very different, and should sound familiar. The white immigrants were held below decks during a six-week ‘Middle Passage’ and on arrival ‘summoned at six and sent to the fields ‘with a severe overseer to command them.’ They were ‘bought and sold still from one planter to another, whipped at the whipping post for their master’s pleasure, and many other ways made miserable beyond expression or Christian imagination.’ (Accounts from mid-1650s).

If, against the odds, the indentured servant survived to the end of his term, by the later 17th century, the planters consolidation of land-ownership made it very unlikely that he’s be seeing his promised 10 acres.

The result should also be familiar: the indentured servants became sullen, docile, displaying an almost childlike passivity (sound familiar? It’s how the slave-masters used to talk of chattel slaves). Eventually though, they reacted as slaves everywhere eventually do: they plotted rebellion.

In 1649 the servants’ plot to murder the planters and seize the island was discovered. Eighteen were hanged, and, in the aftermath, control over indentured servants was tightened further. Under the new conditions, servants required their master’s permission to marry or even leave the plantation; if they struck their master, two years were added to their indentured period; if AWOL from the plantation it was an extra month of servitude was added for every two hours away.

At this point, it is hard to see much difference between the cruelty and control of white indentured servants and the cruelty and control of black African chattel slaves. And indeed, the planters had plenty of reason to fear that the white indentured servants would ally with the black slaves to overthrow them. Something had to be done: in 1661 it was.

The 1661 Barbados Slave Act marks the point at which generalized brutality and cruelty by planters against those who worked for them - white or black - morphed into something even more pernicious: race-based untrammelled, consequence-free chattel slavery.

This is the hard stuff, the point of no return. The preamble asserted that Africans were “an heathenish, brutish and uncertaine, dangerous kinde of people,” so "If any Negro or slave whatsoever shall offer any violence to any Christian by striking or the like, such Negro or slave shall for his or her first offence be severely whipped by the Constable. For his second offence of that nature he shall be severely whipped, his nose slit, and be burned in some part of his face with a hot iron. And being brutish slaves, [they] deserve not, for the baseness of their condition, to be tried by the legal trial of twelve men of their peers, as the subjects of England are. And it is further enacted and ordained that if any Negro or other slave under punishment by his master unfortunately shall suffer in life or member, which seldom happens, no person whatsoever shall be liable to any fine therefore."

Suddenly, life as a white indentured servant, be it ne’er so miserable, was better than chattel slavery. I wonder if they appreciated their ‘white privilege’. They were meant to.